In his 2003 Massey Lecture, the novelist Thomas King—the first person of Cherokee descent invited to be a Massey lecturer—stated: “The truth about stories is that’s all we are.” Stories can transform a culture, but they can also attempt to destroy one. Look no further than the narratives about Indigenous people found in settler-colonial sources which are often little more than destructive fictions.

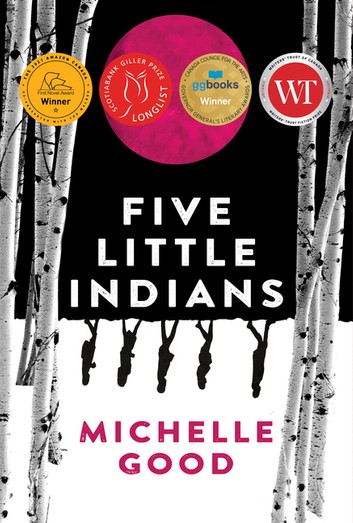

In her first novel, Five Little Indians, the Cree writer Michelle Good counters the toxic stereotypes about Indigenous people that have long dominated mainstream writing, social discourse and the media. Her novel offers a space for Indigenous and non-Indigenous readers to enter the lives of five residential school survivors—Lucy, Kenny, Clara, Howie, and Maisie. When they were small children, they were taken from their homes and placed in a residential, church-run school located in British Columbia. At the Mission School, the children were abused and stripped of their Indigenous heritage. One escapes. Some age out. All five end up at various times on Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

In interviews, Michelle Good notes that she felt compelled to write about residential schools, though she herself did not attend one. Good’s mother and her entire family were not so fortunate. “I’ve been thinking about residential schools and their impacts in many ways since I was a child,” she remarks. “Our communities are suffering because of the harm inflicted in these schools.” Her aim in Five Little Indians is to make those hurtful experiences come alive and to show their damaging long-term effects.

To that end, Good does not dwell exclusively on the residential school system. She certainly exposes the sexual and physical abuse which was rife at the Mission, but the story she tells focuses more on the post-traumatic period and survivorship in the outside world that treats these young people as if they are throwaways.

Good’s triumph as an author lies in her ability to embrace without judgment the various paths her characters take. There isn’t one particular fix or formula that will ensure a release from the horrors they’ve suffered. Kenny, who fled from the Mission at the age of thirteen, moves from job to job, trying to outrun his terrifying memories and his addiction. Lucy embraces motherhood and waits in vain for Kenny to return to the family life they tried to create together. Clara finds her way into the political world of the American Indian Movement. Maisie internalizes her pain and continually succumbs to sordid sexual encounters. Howie, released from prison for almost killing his abuser, ultimately finds peace living on the land.

Still, despite the trauma and cultural erasure that Michelle Good so powerfully depicts in Five Little Indians, the novel ends by affirming the continuity and vibrancy of Indigenous ways. In a final prophetic scene, the author describes Clara hanging three old glass bottles tied with hide on the branch of a poplar tree. She listens to them “tinkling her song of home.”

Five Little Indians is a must read for Canadians. Congratulations to Michelle Good and her debut novel for being named the winner of Canada Reads 2022.

For further reading, see Inanna Publication’s titles in Indigenous Studies here

Five Little Indians by Michelle Good

Harper Perennial (April 14, 2020)

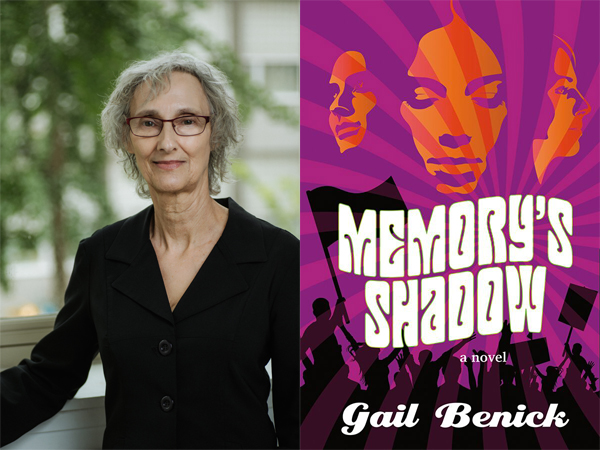

Gail Benick is a Toronto author and educator. Her career as a professor on the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at Sheridan College in Oakville, Ontario, spanned more than three decades. Her debut novella, The Girl Who Was Born That Way, was published in 2015. Gail’s new novel, Memory’s Shadow, was published by Inanna in spring 2021. www.gailbenick.com

I agree Gail. This is an enormously powerful book and a must read for all Canadians trying to understand the impact and damage done by residential schools. The characters and the relationships between them are wonderfully and sensitively depicted.

As always, Gail, terrific review of the book Five Little Indians. Have not yet read the book but for sure will put on my list to read.

Gail, you sensitively and eloquently capture the heart and soul of this must-read novel.

Thank-you for writing sharing. Your review is also a “must-read”,

Thank you Gail, for this thoughtful review of Five Little Indians. As Canadians, we ought not to readily accept stereotypes of Indigenous peoples but rather to have a greater understanding of the long-term effects of Residential Schools. To that end, this book is a “must-read”, with your review inspiring others to do just that.