I recall a few lines of a narrative poem by Nima Yushij, one of my favorite poets. The character of the story, a poor fisherman coming upon a mermaid one stormy night, says to himself: I must follow my own path/no one will take care of me/amidst the turmoil of life/though they may deny, everybody is alone/what will tend to me is my own work.

To be honest, it took me some years to realize that writing is my right path. In fact, my relationship with writing has always been difficult but unavoidable. Despite my innate thirst for stories and my ardent love for literature, in my school years I showed little interest in writing. While I enjoyed math class a lot, I found composition class either stressful or boring. Unlike many teen-agers, I didn’t write journals. But in my first university year, I felt an overwhelming urge to write out the stories inside me. It was out of my control. The result of my first attempt to write a novel, although obtained easily and almost automatically, was thrown into the trash bin. I thought there was no regret in discarding it while I felt confident that I could write my stories anytime I liked.

Such was the start of my writing odyssey. Without thinking about it as a career, I started to educate myself by working with publishers as an editor, translating books, and plunging into world literature. Yet in my early twenties, the whole life suddenly turned upside down with a regime change: social turbulence, political repression, war-time horrors, and severe book censorship. Under totalitarian rule I could publish only two books of fiction and several literary translations during a period of twenty years.

At the age of 45, I immigrated to Canada with the expertise and experience of a research librarian. Soon I realized my professional qualifications could not work for me. I also understood that my literary identity could not be recognized simply because I had no books published in English. During the first couple of years, trying hard not to get stuck in survival jobs, I didn’t have the luxury of enough free time to read and write. As I was determined to reclaim my identity as a writer, I gradually began to translate some of my stories into English and write essays and stories in English. Over the years I succeeded in finding contract academic jobs and opportunities like senior fellowship at Massey College and PEN writer-in- residence at George Brown College.

Unwilling to abandon my mother tongue, I published some works and reconnected with my readership in my home country thanks to the internet and social media. More notably, twenty years after arrival in Canada, I could get my first novel in English traditionally published – although I didn’t know anybody.

Soon after my book was released by a small publisher in Toronto, the pandemic hit. There is little prospect of my book getting attention in CanLit scene. Here and now, I am not an award-wining or best-selling writer; and back home, the regime shows utter disregard for writers like me who challenge censorship. Nonetheless, I don’t see myself as a loser. Despite all ups and down, I didn’t give up writing what I wanted to. This is the greatest achievement for me: ‘amidst the turmoil of life’ I could follow my own path, and my own work ‘will tend to me.’

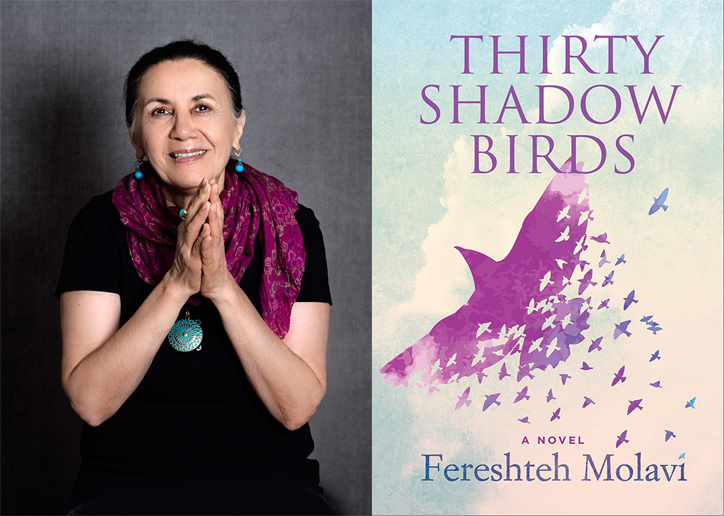

Born in Tehran in 1953, Fereshteh Molavi lived and worked there until 1998 when she immigrated to Canada. She worked and taught at Yale University, University of Toronto, York University, and Seneca College. A fellow at Massey College and a writer-in-residence at George Brown College, Molavi has published many works of fiction and non-fiction in Persian in Iran and Europe. She has been the recipient of awards for novel and translation. Her first book in English, Stories from Tehran, was released in 2018; and her most recent novel, Thirty Shadow Birds, was published by Inanna Publications in 2019. She lives in Toronto. www.fereshtehmolavi.com

ِDear Feresheh,

Greetings from from your humble and obidient subject Ezat. I was thrilled by seeing your picture and your comments on your new book in English. I wish you the best in your great endeavor and I am pretty sure that you will create more literary works of par exellence in the near future. I will be pleased to buy a copy of your book and enjoy reading it. With my best cordial wihes, Ezat

Dear Ezat, such a great pleasure to hear from you, and many thanks for your nice words. I really hope you enjoy reading my novel. All the best, F.