Like many women, I was inspired and empowered by the Me Too movement but it also brought back a lot of painful memories. Most of us have probably encountered a “Harvey Weinstein” at some point in our professional lives. I know I have. This type of sexual predator lurks not only in Hollywood but in any environment where there is a power imbalance, which is most workplaces. So whether you are a waitress, a poet, a sales clerk or an administrative assistant, you learn to acquiesce. You learn quickly not to say anything because he’s “the boss” or he’s friends with so-and-so who is “really important” and besides, maybe you totally misunderstood and who do you think YOU are anyway? So you shut up and the silence strangles you. People like Harvey Weinstein do what they do because they know they can do it; they know that we live in a society that values money and status above kindness and integrity. They believe that their wealth and position entitles them to do what they want to whomever they want and what is worse they know the people around them believe this too.

Today, the working class and the working poor rarely see their lives represented on the big screen but this was not always the case. During Hollywood’s Pre-Code period (1930-1934), movies that came out of the Warner Brothers studio catered to a working-class audience. For a brief moment, blue collar workers, taxi drivers, waitresses, maids and the unemployed could see relatable images of themselves up on the silver screen. It is therefore not surprising that many of these films addressed sexual harassment in the workplace with a bluntness and honesty that is rarely seen in the movies today.

“I related to shop girls and chorus girls, just ordinary gals who were hoping,” said Joan Blondell, one of Warner Brothers’ most prolific stars. “I would get endless fan mail from girls saying ‘that is exactly what I would have done, if I’d been in your shoes, you did exactly the right thing.’”

Blondell plays a hotel maid in the romantic comedy/crime drama Blonde Crazy (1931). In one scene, a lecherous salesman asks for towels and then tries to grab her. Blondell pushes him away and angrily stuffs his merchandise – the pearls of a broken necklace – down the back of his pants. She gives him a swift sucker-punch in the butt before bolting from the room. Although the scene is played for laughs – and the laughs are at the salesman, not Blondell – her character’s frustration is palpable.

Motion Picture Magazine, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Workplace sexual harassment is presented with much more gravity in William A. Wellman’s Night Nurse (1931). In the film, the incomparable Barbara Stanwyck portrays Lora Hart, an idealistic rookie nurse who discovers that the children she has been hired to take care of are being starved to death by their wealthy alcoholic mother’s lover (played by a young Clark Gable). The police and the head doctor refuse to help her so she must save the children on her own – with a little help from the friendly neighborhood bootlegger. Night Nurse (1931) is the epitome of Pre-Code Hollywood and illustrative of the cynicism that many Americans were feeling at the time toward authority figures and Prohibition – the bootlegger saves the day! – but it also serves as an example of the real life violence and harassment that nurses and Personal Support Workers (PSWs) experience on a daily basis (today, Stanwyck’s character would probably be called a PSW rather than a nurse). In one scene, a friend of Lora’s wealthy employer grabs and forcibly kisses her. In another, Gable’s character literally twists her arm and then punches her. For most of the film, Lora’s nurse uniform invites both ridicule and sexual come-ons. If you think that incidents like these only happened in the 1930s or in the movies, think again. In 2017, an Ontario Council of Hospital Unions poll found that 68% of nurses and PSWs across Ontario had experienced physical violence on the job at least once during the year and that 42% had experienced sexual harassment and assault. And those were just the incidents that were reported. Watching Night Nurse (1931), I had the sinking feeling that many nurses and PSWs today would sadly relate to the violence and harassment faced by Stanwyck’s character. Night Nurse (1931) was released eighty-nine years ago – when was the last time you saw a Hollywood movie about a Personal Support Worker?

Other Warner Brothers’ movies attempted to turn the tables on the sexual harassment faced by working class women. In Baby Face (1933), Stanwyck plays an impoverished young woman who, sick of being used sexually by men, decides instead to use men “to get what she wants”: namely, sleeping her way up the corporate ladder of a bank (literally “screwing” the bank – Depression era audiences must have really gotten a kick out of that!). Female (1933) took it one step further: in this delightful film, Ruth Chatterton portrays Alison Drake, an intelligent, no-nonsense woman who is the president of an automobile factory. However Alison is not all work and no play: by day, she is all business but by night she slinks around her apartment in a skimpy gown, serving vodka to her suitors to “fortify their courage”. Her seduction technique involves playing the music from Footlight Parade (1933) on the Victrola and tossing a silk pillow onto the floor. “I decided to travel the same open road that men do,” she candidly tells a friend. When asked whether she’d ever like to settle down and find a husband, she replies “I’d rather have a canary.”

First National Pictures, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

While the shop girls and secretaries who came out to see these films in droves may have smiled and thrilled to the exploits of Joan Blondell, Barbara Stanwyck and Ruth Chatterton, most knew that they themselves would never get away with socking the jaw of a lecherous boss or breaking a bottle over the head of a grabby customer. At best, they would get fired. At worst they would end up in prison. Either way, they would be at risk of never working again. This reality is illustrated in William A. Wellman’s Safe in Hell (1931), a precursor to film noir. In this haunting film, Dorothy Mackaill plays a woman who is fired from her job as a housekeeper after her employer’s wife walks in on him raping her (this story is told by Mackaill’s character months after the assault and she never uses the word “rape”, although it is strongly implied; “rape” was considered a taboo word in the 1930s). Blackballed from finding another reputable job, Mackaill is forced to turn to prostitution.

Although she never worked as a prostitute, my great-grandmother Nellie probably could have related to Gilda, Mackaill’s character in the film. Like Gilda, Nellie worked as a “domestic servant”. Newly widowed in the early 1920s and needing to find employment in order to regain custody of her children who had been put in an orphanage, Nellie answered an ad in the Globe to work as a housekeeper for a farmer. She quickly learned that in addition to cooking and cleaning, the farmer expected her to perform “wifely duties”. Afraid of losing her children again, she acquiesced. In 1928, Nellie was found dead in the field outside of the farmer’s home: the coroner listed the primary cause of her death as suicide from poison.

Whenever I watch Safe in Hell (1931), I think of my great-grandmother Nellie and of all the working class heroines like her, whose stories were spoken in whispers – or never told at all.

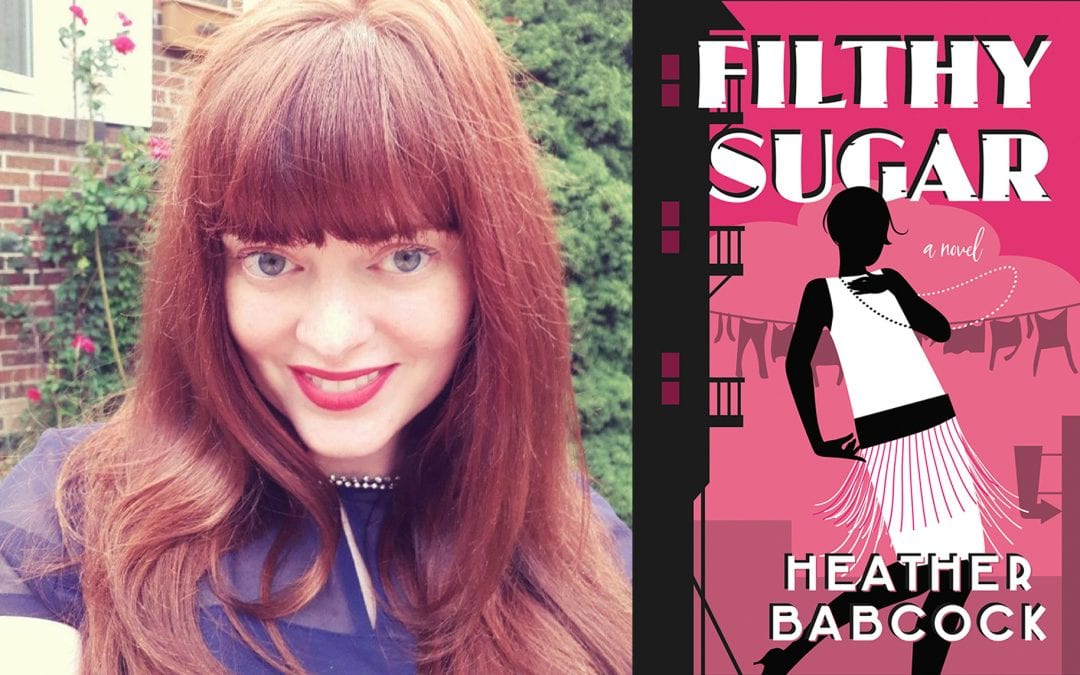

Heather Babcock is an aficionado of Jean Harlow and pre-Code Hollywood films. She has had short fiction published in various literary journals and anthologies including Descant Magazine, Front & Centre Magazine, The Toronto Quarterly, and in the collection GULCH: An Assemblage of Poetry and Prose (2009). Her chapbook, Of Being Underground and Moving Backwards, was published in 2015. She has performed at many reading series including Lizzie Violet’s Cabaret Noir, Hot Sauced Words and thePlasticine Poetry series and is a co-founder of The Redhead Revue and I Got You Babe: An Evening of Music and Poetry. Filthy Sugar is her debut novel. She lives and works in Toronto. www.heatherrosebabcock.tumblr.com

Very well done Heather!!

What a great read this was! I am now interested in watching these movies and looking at this period of time in movie making. Your grandmother’s story was very moving.

Thank you!